Almost all of us dream at some point of living in the country and growing our own food. Few of us achieve that goal but Hilary Elmer made her dream come true. Now, she has a cabin in the woods with a large garden, a few cows and hogs and chickens and a good, healthy life for her family.

Of course, she also makes cheese. She told us, “When I moved to Vermont for my first job out of college, I became friends with an old dairy farmer and was able to buy raw milk from him. I found the New England Cheese Making Supply Company and a passion was born.”

Hilary’s Story

I’m from Ohio. Growing up, I always wanted to live in a place that had longer winters, got more snow and was colder. Be careful what you wish for! I definitely got it.

We love it here though, it’s very wild. Our closest neighbors are moose.

How I got here:

Growing up, I always used to feel like a weirdo. I never fit in. I wanted to live in a cabin in the woods and grow or hunt my food.

My dad taught me his love of the outdoors and American history. He took me hunting from a young age and taught me how to responsibly harvest and prepare animals for food.

Hilary and her father

I shot my first deer when I was 10 years old.

I’m so grateful that during this past year when industrial meat was shut down due to Covid, and families that raised their own meat were on waiting lists for months, waiting for custom butchers to process their animals, I have been able to take care of my own, whenever I want.

Cutting deer meat at age 10

My family moved to Utah the summer before my senior year of high school.

Self portrait done in high school

I graduated a semester early and, that January, got a job with the Utah Division of Wildlife Resources at a lake up in the mountains.

For the next four years, I went back and forth between seasonal jobs with the UDWR at lakes and an elk refuge, the National Park Service as a ranger, the US Fish and Wildlife Service as an environmental education intern, as a reenactor at a living history farm and getting a degree in fisheries and wildlife at Utah State University.

Hiking in Utah’s Wasatch mountains after high school

I made plans to start a small farm while I was in college and I wanted dairy animals to be part of it. I started dabbling with cheese making during college.

I love the mountains out west, but I missed the green back east. My dad’s family had a summer home in New Hampshire when he was a kid, so I grew up hearing stories about how beautiful northern New England is. Upon graduation, I applied for several jobs across New England.

I had known my husband since our first year of college in Utah, and we got engaged literally days before I was supposed to move to Vermont! Thankfully, he followed me and the rest is history.

My husband Kevin is the best. He currently supports our lifestyle by working full time for the Vermont Army National Guard. He deployed to Afghanistan back in 2010, which was the hardest year of my life.

I can’t wait till he retires in a couple of years and we will be full time farmers, plus his woodworking business. He’s the one who encouraged me to get my endangered breed of cows when my goats weren’t working out. I have the passion to be a farmer, but he’s the muscle on the farm.

Now:

We live on 43 acres of maple trees, black bears, and old stone walls. When we bought the land thirteen years ago, I was pregnant with Ephraim, our second child. I remember clearing the land for our house with a very big tummy!

We’re about 15 miles from Quebec. Funny story … Once when my daughter was about four or five, she went exploring in the goat pasture behind the house. I was watching her from the window. When she came back in the house, she said, “Mom! I went to Canada today!!”

View from the dairy

We built a log cabin. Because we had a toddler and another on the way, we were in a hurry to get the house built so we hired a crew to build the shell.

When we moved in, two weeks before our son, Ephraim was born, there was only a subfloor, a single sink running cold water, and the windows were not quite all in place. It was rough!! It gave me an all new appreciation for the pioneers who settled the country.

When we bought land and built a house, I couldn’t wait to get goats!

In 2010

My daughter, Hannah when she was 5 with a Nubian kid

When my kids were younger, I had a thriving goat milk soap business.

In 2011

During my goat years, I dabbled with hard cheeses with spotty success. I stuck mostly to quick and easy cheeses like chevre back then.

I love goats, but they jumped the fence one too many times, and my husband convinced me to give cows a try. I also wanted dairy animals that could be grass fed, no grain. We realized that what we needed was a heritage breed of cows.

Our herd:

When we were researching heritage cows, we found a critically endangered breed in Canada – Lynch Linebacks. There were less than fifty breeding females at the time. There is a Facebook page about them and soon there will be a website – https://lynchlineback.ca/.

They are a great pre-industrial breed that thrives in a low input system. We were able to import a small starter herd of them – the first in the states.

I got my herd as young heifers and a bull. They will freshen their first time in late spring, 2021.

I tried a couple of other breeds before we got them – a Dexter and a Milking Devon. I like my Linebacks best. They are calm and sweet.

My Lineback bull when they arrived in 2019

I was scared to keep a bull, which we had to do because we need to breed true to help conserve the breed. But so far, at a year and a half old, he’s a puppy dog. I’m hoping to have heifers, bulls, and semen straws to sell in a few years to establish the breed here in the states.

I take pride in moving my cows to fresh pasture each day, building the soil and keeping my herd naturally healthy. Regenerative farming is good for the environment, the consumer, and the animal.

My relationship with my Lineback cows is beautiful and symbiotic. Honestly, they don’t really need me. I believe that if they roamed freely, they would do just fine.

But, with my stewardship and management, their grazing causes the pasture to improve each year. I am using them to turn young woodlands into silvapasture, which is the most productive biome not only for livestock, but also for wildlife.

Bears, deer, rabbits, foxes will all benefit from my cows’ presence. Each year of grazing increases the organic matter in the soil and the depth of topsoil. Water penetration and retention improves.

Every acre of rich topsoil pulls tons of carbon out of the atmosphere. All of this while providing nutrient-dense food for my family and community. And the cows are happy to do it!

Because we want to help preserve the breed, we decided that we will keep a larger herd than we need for our family’s use. Therefore, we are going to open a micro dairy within a few years.

Our dairy:

We’ve already got the building mostly built, and a milking machine and a 33 gallon bulk tank. I plan to sell raw milk, and eventually scamorza cheese, butter, and yogurt.

My bulk tank is still wrapped from shipping because the milk room isn’t quite finished yet

The outer walls of the dairy aren’t finished, either, as you can see.

We are going to build the outer walls with cordwood masonry, which is essentially using wood as bricks with mortar between. The cheese room is still very far from finished. Currently, it houses my husband’s woodworking tools.

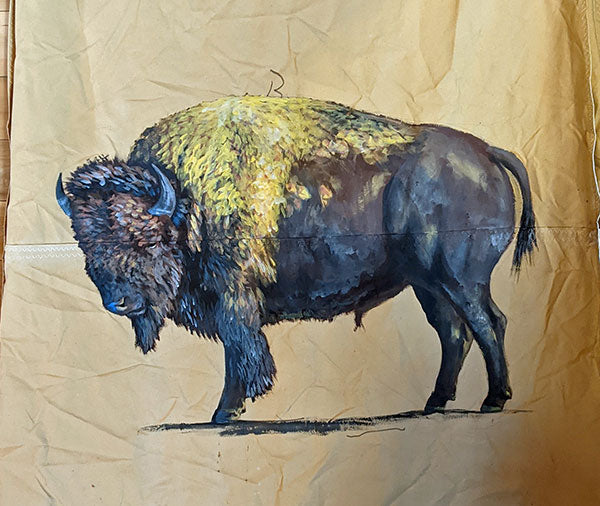

My logo that I drew for my dairy, Between the Trees Heritage Dairy

Our cheese:

Now that I have cows, and I have more time to devote, I have had lots of fun perfecting hard aged cheeses. I have developed my own Alpine style cheese.

Alpine – my favorite. It’s roughly based on Gruyere

I have made some cheddar, some washed curd cheeses, brie, and even Hispanico in an esparto grass mold I got from a Spanish Etsy seller.

Hispanico

I try to make the ones I like over and over again to work out all the bugs.

Alpine style cheese

Scamorza is the one I plan to sell when I go commercial.

Scamorza has a mild, Provolone type flavor. It melts like a dream.

We smoke it in an electric smoker that we normally smoke pork in. Sometimes, I melt a slice and just eat it gooey and dripping.

We tend to eat scamorza a week or two after make. Hanging in my kitchen which is warmer and drier than a cave, it dries out if aged over a month.

For such a young cheese, it has a developed flavor and texture, probably because of the stretching process.

Scamorza

Reasons to sell scamorza are that it doesn’t require a state inspected cave or long term aging. The downside is that because it’s aged less than sixty days I will have to make it with pasteurized milk. But honestly, the curds get hot enough during stretch that they are pretty close to pasteurized anyway.

I really enjoy making and shaping scamorza, but boy there is a learning curve! I’ve probably made a dozen batches, with four per batch, and I’m still learning!

Someday I will have an expensive industrial press when I sell cheese, but currently for home use, this Dutch press is awesome. I’m able to make up to 10 lb cheeses in it.

My son Ephraim (13) likes to help me on the farm. Most of the cheese that I make is for him. He prefers scamorza because it has a less complex flavor than my aged cheeses which develop mold on their rinds.

Ephraim broke his arm playing soccer with a friend. He tripped and slammed his shoulder into the frozen ground. It’s all better now.

When I open the dairy, he is going to work for me – caring for the cows and processing milk into cultured products.

Ephraim has helped make cheese a few times. These photos are of him making scamorza for a talent show.

Ephraim cutting curds that have reached the right pH to heat and stretch for shaping.

Ephraim is in the seventh grade at Lowell Graded School, a great little school with about 100 kids from pre-K through eighth grade.

What everyone loves about him is that he is a sweet kid who always asks people how they are doing and tells them to have a great day. He makes everyone feel good about themselves.

Ephraim: My mom makes cheese, and I really got interested in it from watching her make it. I like to eat cheese. I like eating fresh curds. People who don’t make cheese don’t get to eat curds fresh. My most favorite kind of cheese is smoked scamorza because it’s a small cheese. Bigger cheeses don’t taste as good toward the middle. I like it’s texture. It’s fun to make because you stretch it.

Our milk:

My Lynch Linebacks are not quite milking yet. Currently I am buying unhomogenized milk from a small local dairy to practice making cheese every week.

It’s pasteurized, which allows me to play with “clean slate” milk, but I will use raw milk once my girls are producing.

Our cave:

I have several LEM meat totes and lids with holes drilled for ventilation. They are in my basement, which hovers in the high 40’s during the dead of winter, to about 60F in mid summer.

The cheeses age differently depending on the season. They tend to grow more diverse molds when it’s warmer, but they always taste good.

My husband really wants to build me a cheese cave in the side of a hill someday. If we ever get to that point, you can bet I will make some pretty awesome Alpine cheeses in it!

Other interests:

I used to think that I would have to do lots of canning and freezing of food to preserve the harvest, but between my root cellar and fermenting in Fido style jars (with clamped lids), the only thing I can is ketchup and maple syrup.

(If you are wondering, no, we don’t make our maple syrup. I have several times, but until my husband retires in a few years from the army, and can help with doing a larger amount, I’m happy to buy it wholesale from a neighbor.)

Squashes like a warmer winter storage than root veggies, so, they winter in my kitchen.

Boston Marrow squash in 2015

Fermenting is easier than canning because there’s no boiling water bath involved. Just shred the veggies, pack them in the jar with salt, close the lid and you are done.

Fido type jars do the best job of preserving ferments that I have found. Their solid, air tight seal doesn’t allow oxygen in, so they last through the next spring.

I even ferment tomatoes into tomato paste, which is lots easier than making tomato sauce.*

We raise pigs and a few chickens for eggs. Last year I raised Mangalitsa-cross pigs for the first time and I loved them. Mangalitsas are also called sheep pigs because they have a uniquely curly coat – they look like sheep with a snout.

My Mangalitsa boar

Not only do they have more fat – and it’s the most DELICIOUS fat you have ever tasted – but because they are slower growing, they don’t require the same high octane diet that faster growing breeds require.

These are my Manga-crosses that convinced me that I like Mangalitsas, spring 2020.

I’ve always grown my pigs in the woods, moving them every few days, requiring them to forage for a large amount of their food. Other breeds acted like they were starving (even though they weren’t), but the Mangalitsa crosses are perfectly happy foraging.

Manga-crosses

Last fall I bought a full Mangalitsa boar, and two Idaho Pasture Pig gilts (young sows). IPP’s are another breed known for being good foragers. We are going to start breeding our own pigs and selling Manga/IPP crosses.

Idaho Pasture Pig gilts. Note the upturned snouts that helps them graze rather than root.

My art:

The job that first brought me to Vermont in 2002 was working for the Vermont Institute of Natural Science as an artist, upgrading educational materials. I even illustrated a book for them, called Small Wonders.

I was hired to paint the window murals by a friend who had a store in Johnson, VT.

During the quiet of winter, I still do art.

My friend has a teepee and he barters paintings on the removable interior panels for chimney sweeping.

I plan to sell paintings of my farm someday, when we have a farmstead store.

For NECS:

Over the years of my cheese making adventures, I’ve had a lot of questions. Jim Wallace (your technical advisor)* has taken the time to answer every one. I like to research cheeses from around the world, and compare recipes by different makers. I frequently visit your website (cheesemaking.com) to read Jim’s detailed recipes and instructions. It’s proven to be a valuable resource. (Note: Jim is always there to answer your questions at jim@cheesemaking.com).

Fermenting tomatoes for tomato paste

*To make fermented tomato paste:

Chop tomatoes in halves or quarters and toss them in a bucket.

For every two pounds of tomatoes, add one tablespoon of non-iodized salt.

Stir the salt in, then cover with a 5 gallon bucket paint strainer such as you can buy in the paint section of a hardware store. This will keep bugs off.

Every day for at least a week, stir the tomatoes. You will notice something that looks like white mold on top. It’s not mold, it’s kahm yeast and is harmless.

Once the tomatoes have bubbled and the bubbles subside, and it’s more of a slurry than chunky, it’s time to strain them.

Run them through a blender, then a food mill, to remove seeds and peels. Even if you don’t mind seeds and peels, you still need to do that. The one time I didn’t, that whole batch bothered our tummies.

Finally you can drain it, just like draining a soft cheese.

Put the strainer in the bucket and have a helper hold it in place while you pour the tomato slurry in.

Rig it up so that it is suspended above the bucket and let it drain for at least 24 hours.

Once it has finished draining and has a nice pasty consistency, spoon it into 8 oz jars.

Make the surface as smooth as possible and leave at least a half inch of head space. Top with olive oil to keep air from contacting it.

Store in a cool place like the basement. It will keep at least a year.

Be sure to add water when you use it because it’s thicker than sauce. It’s also a bit tangier than unfermented sauce, but it’s good. You can add garlic and herbs during the ferment if you like.