|

| The quake struck the Emilia Romagna region 30 miles north of Bologna |

Millions of dollars worth of cheese ruined

Our hearts go out to the people of northern Italy for their terrifying

experience with the earthquake Sunday, May 20.

At this time, 4500 people are displaced, many are injured and at least 7 are dead. Architecture which has endured for centuries is rubble.

|

| This clock tower later came completely down during an aftershock. (Source: Reuters) |

|

| AFP Photo / Pierre Teyssot |

|

| (Photo: AFP / Getty Images) |

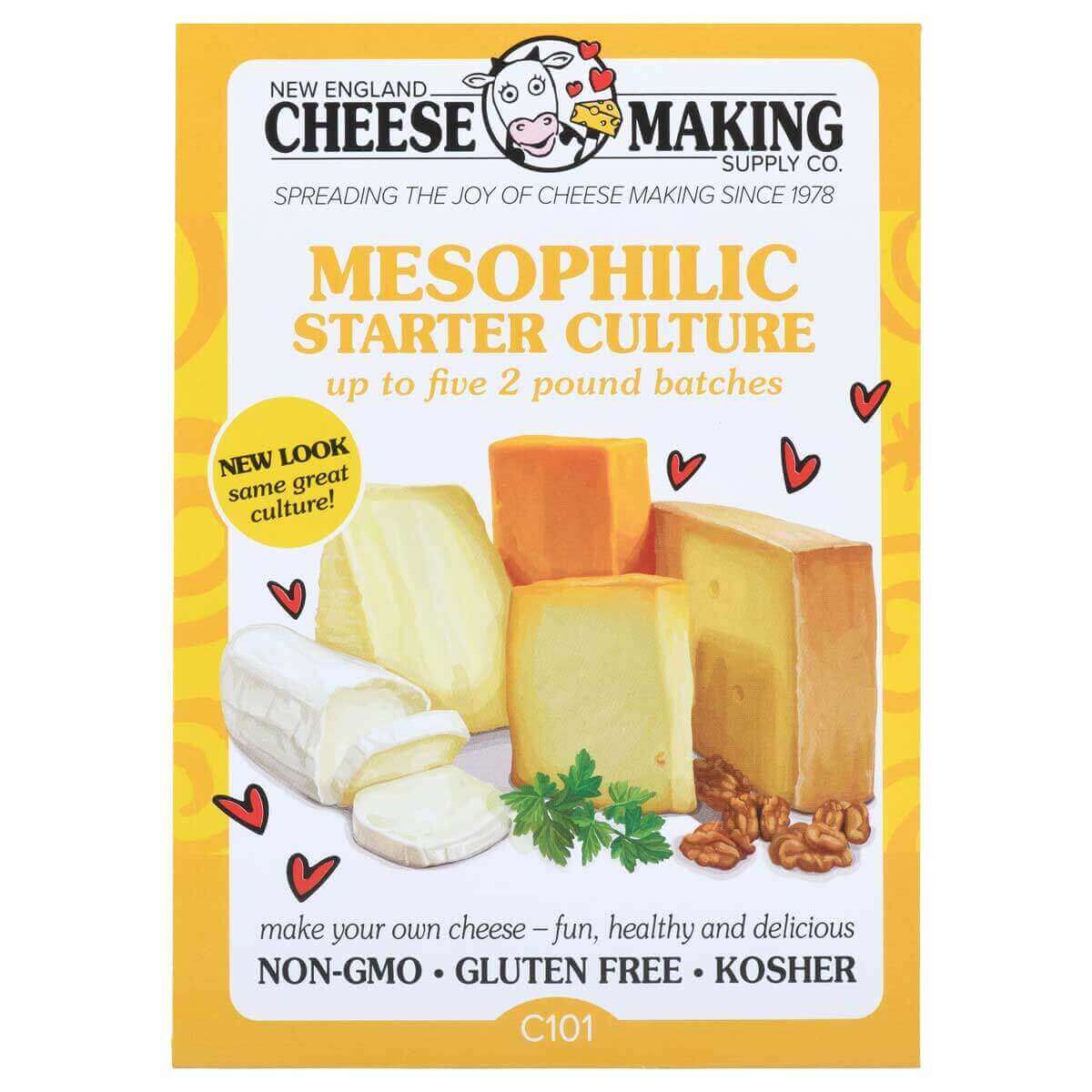

Our sympathy is for everyone involved, of course. However, because we are cheese makers, we identify in particular with the producers of Parmesan and Grana Padano cheese. That area of Italy, north of Bologna, is the Protected Designation of Origin (PDO) for Parmesan and part of the PDO for Grana Padano. (That means it is the only place in the world where Parmesan can be labelled as such.)

|

| Photo by Giuseppe Cacase, AFP, Getty Images |

During the earthquake and the aftershocks, thousands of wheels of cheese fell from their shelves in the warehouses of the area with millions of dollars worth of damages. It is estimated that 10% of Parmesan production and at least 2% of Grana Padano production has been impacted.

|

| Oriano Caretti looks at the overturned shelves with Parmesan wheels in his Parmesan cheese factory in San Giovanni in Persiceto, Italy, Monday, May 21, 2012. (AP Photo/Luca Bruno) |

There were 10 damaged warehouses with 300,000 wheels of

Parmesan-Reggiano and 100,000 wheels of Grana Padano in them. (Each

wheel weighs an average of 88 pounds.) Half of them are estimated to be

at least a partial loss. It represents the work of 7 companies for 2 years.

|

| Photo by Giuseppe Cacase, AFP, Getty Images |

Some of the wheels are being salvaged and moved to other warehouses, and some will be sold for grating and for packaged foods, but that will be only a fraction of their full value as aged Parmesan-Reggiano.

|

| Photo by Giuseppe Cacase, AFP, Getty Images |

From Reuters:

cooperative in the town of San Giovanni in Persiceto.“We may be able to sell some of it for use in melted cheese products but that has only 20

percent of the value of the real thing,” she said by telephone.She said 22,000 wheels of hard cheese fell over in their warehouse during the quake.”We still can’t see the floor in many places,” she said. “We will be lucky if we can somehow save half of it.”Production of milk used for cheese making in the area was also affected because many cows died in the collapse of stables or were left traumatized by the quake and its aftershocks, affecting the output and quality of milk.

The day after the earthquake, and now, after all they have lost, cheese makers in the area are making cheese. They have no choice, because the milk keeps coming.

Supporting the Cheese MakersRicki (our Cheese Queen) had a good idea- If they could market and sell the damaged cheese as Earthquake Cheese, we could buy it as a way of supporting the cheese makers from that area.

Before the Earthquake

|

| Photo credit: J.P. Lon |

If you are interested in the process of making Parmesan and Grana Padano, there is a delightful segment in Cheese Slices by Will Studd (a series of videos) about making it. These large wheels of cheese are made in over 500 small dairies, each of which makes an average of only 10 per day. They are then aged in warehouses operated by a consortia (since 1955). They are aged for different lengths of time up to 30 months. While aging, they are turned and rubbed by large robots controlled by computer.

It’s an unusual system and it’s difficult to describe, so I found the post below which I think captures the feel of how they make Parmesan:

|

| Justin Watt in India during his trip around the world |

A taste of Parma

By Justin Watt at Justinsomnia

July 11,2010

life you wish you could do (like travel around the world). He has a great blog (Justinsomnia) where he explores ideas about food,

travel, technology and the outdoors.

Parma started out as a whim. I mean, when people think about visiting Italy they usually think: Rome, Florence, Venice, Naples, Milan—not Parma. But while looking at the cities between Florence and France, I thought to myself, “Hey we like Parmesan and Prosciutto, let’s go to Parma!” At least I figured we’d get to taste some cheese.

In the end we spent four nights at the friendly, family-owned Camping Arizona, we visited each of the Musei del Cibo (the incredible, I-can’t-believe-they-actually-exist “Museums of Food”: Parmesan, Prosciutto, Salami, and Tomato) and we discovered something even better than prosciutto: culatello. Though we never ended up in the city of Parma itself, we fell in love with the countryside. And it’s where, I can say with confidence, that I finally started to feel comfortable driving with a stick-shift.

|

| This is Parmesan country |

The real gem of our trip to Parma was visiting C.P.L., a working caseificio, one of over 400 independent “cheese factories” within the Parmigiano-Reggiano Consortium. Each makes what we commonly refer to as Parmesan: the famous hard Italian cheese that comes in 40kg (88lbs) wheels and fractions thereof (not the stuff that comes in green cylinders labeled “Kraft”).

|

| A traditional copper kettle for making Parmesan cheese next to a modern one at the Museo del Parmigiano-Reggiano in Soragna |

|

| Inside a Parmigiano-Reggiano cheese factory |

Milk arrives at the factory twice a day. The evening milk is left out overnight to allow the cream to rise to the surface. The cream is removed in the early morning to make butter (long-time readers might recall my previous post: The King of Butter), and then the “skimmed-milk” is combined with the morning’s whole, full-fat milk to make that day’s cheese: about 1,200 liters (317 gal) in each conical copper kettle.

|

| Using a spinatura to cut the curd into rice-sized pieces |

|

| The cheese maker monitors the temperature and checks the curds |

A portion of the whey from the previous day’s cheese making acts as the starter culture (kind of like bread making). Every day some whey is reserved for this purpose, while the excess goes to the pigs used to make prosciutto. This is not only a happy-accident—the DOC regulations for Prosciutto di Parma stipulate that the pigs must be fed whey and other waste products from the production of Parmigiano-Reggiano cheese.

|

| Whey being reserved as a starter for the next day’s cheese |

After being cooked, the entire 90kg (198 lbs) mass of cheese curds is lifted out of its whey by hand with a giant cheese cloth. It’s immediately cut in half, forming two 45kg (99 lbs) “twins,” each of which will become a wheel of Parmigiano-Reggiano cheese.

|

| Cutting the 90kg (198 lbs) mass of cheese curds into “twins” |

|

| The twins draining |

|

| Lo-tech cheese presses |

Once the wheels have dried for several days, they are moved to the brining tanks, where they float in salt-saturated water for more than 3 weeks. After that they are brought to the aging room, where they hang out for a minimum of one year, losing about 5kg (11 lbs) of mass in the process.

At that point each wheel of cheese is inspected, primarily by sound, to determine if it deserves the name Parmigiano-Reggiano. Some cheese can be sold shortly after this point. We tasted some 18 month Parmesan and found it to be rather bland, like a weak Emmental. However, the cheese that’s been aged at least 22 months (what most people know as Parmigiano-Reggiano) was something else: moist, tangy, and almost fruity. What a difference those 4 months make.

|

| Wheels floating in the brining tanks |

|

| Cheese branded (inspected and approved) and aging |

|

| Lots of cheese |

|

| Lots and lots of cheese |

|

| The finished product |