Before you get completely grossed out by this post, please bear in mind that mites are everywhere – in the air, the water, on the land. They are in most of the grains and flours we eat. In fact, they are a very important part of the carbon cycle, helping to decompose organic matter by eating mold. When they aren’t on cheese, they are called ‘storage mites.’

Photo from Pest Management Handbooks

Mites are not a problem for most home cheese makers. They become an issue only with the longer aged cheeses like the Alpines, Cheddars and Goudas. Mites aren’t even interested in these particular cheeses until they have aged for a couple of months, so you have plenty of time to perfect your strategy.

Stamp in Great Britain, released in 2009.

A Bit of History

Cheese has been made for at least 7200 years and mites go back much further. So, it’s safe to assume that mites have been eating cheese right from the ‘get go.’ Why wouldn’t they?

In the nineteenth century, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (best known for his Sherlock Holmes books) wrote a poem about them:

A Parable

Written by Arthur Conan Doyle in 1898

The cheese-mites asked how the cheese got there,

And warmly debated the matter;

The Orthodox said that it came from the air,

And the Heretics said from the platter.

They argued it long and they argued it strong,

And I hear they are arguing now;

But of all the choice spirits who lived in the cheese,

Not one of them thought of a cow.

In 1903, a film was made showing mites eating a piece of Stilton cheese. It became the first film ever banned in the UK because the government thought it would be bad for the cheese business. Here’s the film that caused the problem:

What are they?

If you have ever aged a natural rind cheese, you might have noticed that a fine dust seemed to appear on the rind. If you had brushed it off and looked at it with a magnifying glass, you would have seen it move. That dust consists of mites and their, well, feces. Eeeewww!!!

Those little mites are members of the spider class and the tick family.

1 Chelicerae, 2 Palps, 3 Salivary glands, 4 Gut, 5 Excretory (Malpighian) tubules, 6 Anus, 7 Ovary or testes, 8 Air-breathing tubes (tracheae), 9 Central ganglion, 10 Legs, 11 Hypostome. (From Wikipedia)

There are many different kinds of cheese mites, including Tyrophagus putrescentiae which means ‘putrid cheese eater’ in Greek. They eat the fungi on the cheese rinds and eventually they burrow further into the paste of the cheese.

Tyrophagus putrescentiae. The strands they are eating are fungus on top of the cheese, not the cheese itself. (Photo from Wikipedia)

Mites love the conditions in cheese caves because they prefer temperatures of 45-55F and they love to eat mold.

What are they good for?

Some cheeses depend on mites to achieve their flavor and texture:

Mimolette is actually injected with mites during the aging process. In 2013, this cheese was banned by the FDA from entering the US because they deemed it a health hazard and a potential allergen. (FDA guidelines allow for only 6 mites/square inch.) There was really no evidence to support this (other than possibly some dermatitis when handling) so the ban has not been enforced since 2014. Mites are injected into Mimolette because they create a sweet, caramelly flavor.

Mimolette

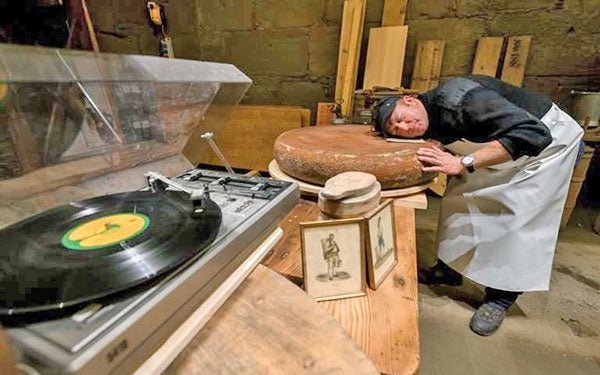

Milbenkäse, (mite cheese) from Germany. This cheese is placed in a box with flour and cheese mites. The mites prefer the flour, but some of them also flavor the cheese.

Milbenkäse. Notice the “dust” around the cheese. (Photo from Wikipedia)

Any long aging cheese with a totally natural rind like Cantal or Comte will attract mites. When the rind is pitted, you can usually assume that the mites have left their mark.

How do we keep them off our cheese?

Our main goal is to keep them out of the cave by keeping the cave clean. But, once they are in, our goal is to keep them from getting into the paste of the cheese because, at that point, there is nothing we can do.

Waxing, of course keeps them out, but sometimes you want the taste of a natural rind.

Vacuum sealing will keep them away, but many folks can taste the plastic in their cheese.

Oiling or clear coating your cheese keeps them out unless you ease up on your applications for long enough to let them in.

Bandaging doesn’t help because the mites can get through.

If you want a totally natural rind:

Rub your cheese regularly with a salt and vinegar solution: 1 T salt, 1 T vinegar and 1 cup water.

Lower the temperature of your cave to 46F if that won’t affect any other cheeses. (If the mites are already there, this might not have much effect.)

Regularly brush your cheeses off, but be sure to do this in a separate room (or into a sink) and not on the floor of your cave.

Vacuum your cheese with a small vacuum you have designated for this purpose.

Position your cheeses on their sides because mites prefer the dark, hidden areas where the cheese meets the shelf.

Dust Food Grade Diatomaceous Earth (DE) on the rind of your cheese with a fine sieve. (This suggestion comes from Gianaclis Caldwell in her book Mastering Artisan Cheese Making). It dehydrates the mites. As with the methods above, it must be done before the mites get into the paste. Caldwell recommends wearing a mask because although it isn’t toxic, it’s never good to get a fine powder in your lungs. You can also sprinkle it in your cave as a deterrent.

Do you have a way to keep the mites at bay? Share it with us in the comments or send it to jeri@cheesemaking.com.

Photo of cheese mite made public by Clouds Hill Imaging. It looks huge in this picture, but you generally can’t see mites without a magnifying glass.